By Sam Bleakley

A fresh array of surf films like Sonic Souvenirs by Kai Neville, Surfing by Dan Scott and Lost Track Atlantic by Ishka Folkwell, affirm that the genre is as alive and vibrant as ever, with many leading surf companies such as Vans and Need Essentials funding the work as branded content, free to view online. But what about British surf filmmakers? We have plenty to celebrate. Notable talents include Luke Pilbeam and Greg Dennis regularly making emotive short films for Finisterre. Seth Hughes and Sam Breeze are up-and-coming talents with a fantastic portfolio of work already released. While Joya Berrow and Lucy Jane’s outstanding Surf Girls Jamaica has been globally acclaimed. Wavelength magazine have been showing international classics at open-air drive-in cinema nights in Newquay to set ablaze the surf film stoke, and the annual London Surf Film Festival, founded by Demi Taylor and Chris Nelson, has long been a big supporter of both international and British surf filmmaking. Ask any British surfer from any generation, and they will surely agree that seeing surf films by British filmmakers is hugely inspiring. But where did it all begin?

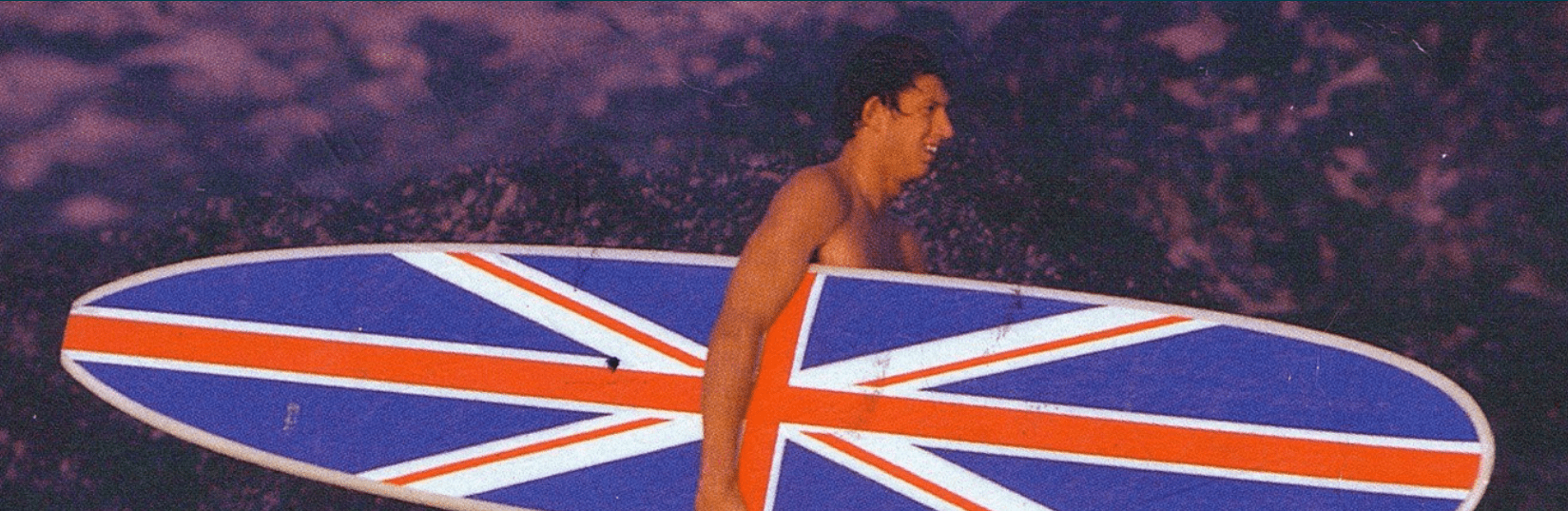

The first person to really focus on British surf filmmaking was Rodney ‘Rod’ Sumpter. Watford born Sumpter was Britain’s first surfing superstar, winning British and European titles in 1966, and reaching the finals at the World Surfing Games in San Diego on his British built Bilbo signature model with a Union Jack pigmented across the deck. He flushed British surfers with national pride and a belief that maybe one day we could create a World Champion. The Sumpter family were part of a wave of emigrants swept abroad in 1952 on the so-called ‘Assisted Passage’ or ‘Ten quid ticket’ to Australia, escaping post-war Europe to begin a fresh life ‘down under’. Based at Avalon, on Sydney’s northern peninsula, by 1962 Rod had become a national stand-out, and that same summer four Avalon Life Saving Club members (Bob Head, John Campbell, Warren Mitchell and Ian Tiley) where surfing throughout Cornwall whilst working the lifeguard season in Newquay. In 1963 Rod won the Australian National Junior Title. His loose and lanky style was almost identical to soon-to-be 1966 World Champion Nat Young. When Californian Bruce Brown commissioned Sydney based Paul Witzig to shoot the Australia footage for The Endless Summer film, Witzig asked Nat and Rod, two of Australia’s most talented youngsters, to feature. The Endless Summer became a global hit, and Rod was inspired to get into filmmaking.

In 1964 Rod travelled to California, quickly developing close connections to the American heart of the surfing industry. But he also wanted to travel to Europe, and flying to France on a trip to surf the famous waves at La Barre, Biarritz, Rod saw beautiful waves wrapping around the crystal clear waters of Jersey. Eager to explore the potential, and curious to check out his British roots, he had heard from Jersey surfer, Gordon Burgis, that there was an International event sponsored by the cigarette company Players Gold Leaf at St Ouen’s. Rod easily won the prestigious event, spent the summer surfing through the Channel Islands, Cornwall and France, and fell in love with the European culture and environment. Within a year he decided to move to Cornwall.

In Newquay, Rod met Simonne Renvoize, whose father, Jimmy, owned a photographic and filming shop. They started filming throughout Britain and Europe with a super-8mm camera, editing the footage into Come Surf With Me (1967). Marketing the film to beach goers and in local pubs with fliers and posters, they would pack out church halls rented throughout Cornwall and Devon. Simonne had a strong business head and was extremely talented behind the lens, filming most of the footage of Rod surfing. The influence was profound. Not only were they pointing the camera at British shores, which was a great boost to self-esteem, but they were also driving around the country taking the surf films to all the emerging pockets of British surfing. The country got to see the footage, and meet the best surfer in Britain.

Rod Sumpter made seven films between 1967 and 1979, logging his widespread travels, the growing national scene and the shortboard revolution. With Surfing in Mind (1968) and Freeform (1970) were in the upbeat style of the Californian films made by Bruce and Bud Brown. While Oceans (1971) and Reflections (1973) had a psychedelic feel, in the flavour of John Severson’s Pacific Vibrations (1970). White Waves (1979) and Hawaiian Surfari (1979) were regularly shown on the British cinema circuit, and Rod’s footage of the young tube riding specialist, Rory ‘The Dog’ Russell, at Pipeline, Hawaii, appeared as a sequence in Alan Rich’s epic Salt Water Wine (1973), and a famous Old Spice (aftershave) television advert.

Through Rod’s contacts with filmmakers, Simonne Renvoize, Paul Holmes and Alan ‘Fuz’ Bleakley also showed the latest surf films around the UK with Aquagem Surf Flicks. These included Hal Jepsen classics Cosmic Children (1970) and Sea for Yourself (1973) and Alan Rich’s Saltwater Wine (1973). The impact of these films helped to educate British surfers in an era when cheap travel just wasn’t available. “You wouldn’t believe the level of stoke at these showings,” said Fuz. “People would hoot, gasp and applaud at every move. On Saturday night they would be watching Rory Russell at twelve feet Pipeline, and would be so fired up they’d rush out to surf two feet slop at any beach early the next day and have a brilliant session.”

While Simonne did not surf, she had a long affair with surfing and the ocean, and her networking talents persuaded George Greenough to show his films, Crystal Voyager (1973) and The Innermost Limits of Pure Fun (1969), at the Electric Cinema in Porobello Road in London, where they had packed audiences. Greenough himself had persuaded Pink Floyd to allow the use of their music on the in-the-tube sequences from Innermost Limits. It was a sensation. Greenough had strapped a camera to himself and shot the first genuine in the tube footage, with Floyd’s ‘Echoes’ providing the perfect backdrop.

In 1969 Penzance surfer John Adams and Australian Dave ‘Stickman’ O’Donnall also started showing surf films. While Adams’ venue, the Winter Gardens, was headlining the best contemporary music, including The Who and Fleetwood Mac, surf film showings became the social pinnacle of the local surf scene. In 1975 John showed the widely acclaimed Tubular Swells by Dick Hoole and Jack McCoy. And by 1979 John had formed a film company, ThreeSFilms, and made seven surf films up to 1992. ThreeSFilms also became a primary distributor of surfing VHSs then DVDs in the country. John Adams’ Taking Off in 1981 is a classic, following the groundbreaking launch of British surfers Nigel Semmens, Steve Daniel and Ted Deerhurst’s professional careers.

In 1990 ThreeSFilms toured international classics Surfers the Movie and Rolling Thunder around Britain to filled cinemas. Then the VHS became the dominant way for surfers to consume surf films. Most impactful were Taylor Steele’s Momentum videos, showcasing a group of young Americans spearheaded by Kelly Slater, Rob Machado and Shane Dorian, eclipsing the power surfers who went before them with previously unseen acrobatics to a high-octane California-punk soundtrack. A new generation of surfers could now rent or buy a VHS video, and then a DVD, and stay at home.

Cornwall got an exciting slice of the British film industry when Carl Prechezer filmed Blue Juice in 1995 launching the career of Catherine Zeta Jones. Former British Junior Champion Jamie Owen did the surfing sequences (filmed in the Canary Islands), doubling as lead character JC. But most of the film was shot in Mousehole, Newlyn, Hayle and St Ives, and many west Cornish surfers had a role: for example Chris Ryan played the ‘silver surfer’ in the party scene, with his aluminium board, while Essex Tyler had a few lines as a local ripper, and Steve Jamieson played the lifeguard.

By the late 1990s and into the 2000s independent surf films were continuing to thrive from the likes of Andrew Kidman, the Malloy brothers, Jack Johnson and Jason Baffa, often shot on 16mm cameras with excellent indy music soundtracks that helped launch the careers of many musicians. Self-funded, these films inspired a resurgence of the screening tour, and the ultimate rise of the international surf film festival, from Tyler Breuer’s New York Surf Film Festival to the London Surf Film Festival. Aside from fostering stoke and inspiring a new generation of surfers and creatives still going strong today, these festivals continue to help raise the profile of filmmakers, many of whom have dedicated three years into a single project, injecting more and more into the rich tapestry of surf films. And long may it continue.