From laidback go-with-the-flow attitudes, to post-punk-hipster, lifestyles have been shaped around the ‘cool’ of surfing. Today there are over 30 million surfers in the world, a rainbow spectrum of ages and nations. Surfing is used therapeutically to treat post-traumatic stress disorder and to channel the energies of otherwise wild kids. Surfing is tactile (immersed in water) and so surf culture has mirrored this, spawning a visual feast of photography, fashion, graphics, film, music album covers and posters, all linking back to the addictive feel of a board and that irresistible sensation of riding a wave.

When the ocean-roaming Polynesians settled Hawaii in 400AD, stand-up surfing developed into a complex cultural practice. Surfing was ‘the sport of kings and queens’ - hierarchical, not even a meritocracy (where the best riders could claim the best boards) and certainly not a democracy as it is today, where any level of surfer can own any kind of board. The Hawaiians wrote love stories around surfing. And surfing was feminised - the ancient break Kekaiomamala (The Sea of Mamala) was named after a ladies champion. The board was her status symbol. One Hawaiian legend tells of a local enticed by a chieftess to ride alongside her at a Waikiki break reserved for royalty. He was nearly executed by the ruling chief, saving himself only after he was able to skewer 400 rats with a single shot. The democratizing of surfing is one of the great success stories of post-war America, where, in California in the 1950s, surfing gained an identity as a sport where ‘all can be kings and queens’.

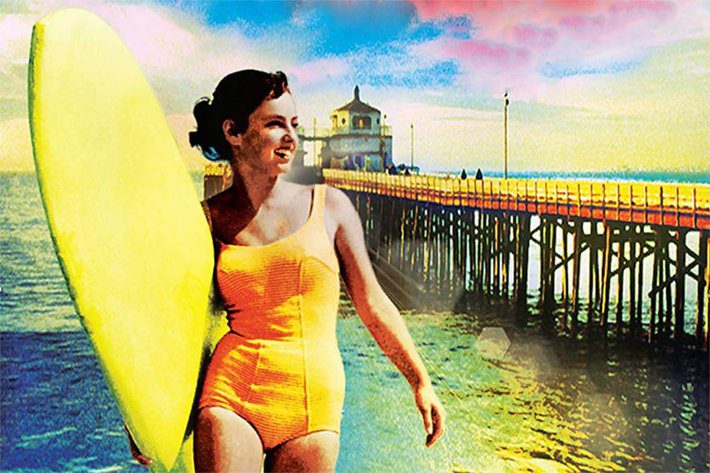

In the breathing space before the Vietnam War, California was about aspiration, upward mobility and the fizz of the new. The crashing ocean, with its ozone-filled spray, became the playground for the young. And ‘extreme sports’ were born at this time, putting adrenalin and style into the mix. The arts were also enjoying an explosion of innovation. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) was published in the same year as Frederick Kohner’s Gidget (1957), relaying the story of his daughter’s (Kathy ‘Gidget’ Kohner) summertime learning to surf in Malibu, Los Angeles. Putman Books sold the film rights for Gidget to Colombia Pictures, and the first Gidget movie (1959) featured Sandra Dee and James Darren, with sensual images of surfing and the explosive bikini (named after the Pacific atoll testing ground of the atomic bomb).

The ‘cool’ new surfing performance repertoire was called ‘hotdogging’, modelled in a pioneering 1959 film by Bud Browne - Cat on a Hot Foam Board - a take on Tennessee Williams’ play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955). While Sal and Dean were dancing ‘mambo jambo’ in Mexico, in Kerouac’s On the Road, Californian surfers were ‘hanging ten’ and ‘shooting the curl’, before also heading to Mexico through surf travel, described as ‘loose’, ‘relaxed’, ‘open toed’ and of course ‘cool’ in Bruce Browne’s Barefoot Adventure (1960) and Surfing Hollow Days (1961). Their surfboards were bright and beautiful things, echoing the revolutions in painting brought by the Abstract Expressionists.

The development of simple, light roof racks and availability of cheap automobiles and smooth asphalt highways meant that inland (‘valley’) surfers could hit the coast, perhaps in a Ford ‘Woodie’. So began the need for wave forecasting, an intuitive surf science of meteorology and expert coastal geology. Locals might say ‘You should have been here yesterday’.

With the emerging surf culture came language (‘dude’, ‘rad’), ‘shaka’ signs, reverberating electric guitar and drum based surf music (Dick Dale, the Surfaris), clothes (Hawaiian print boardshort baggies, heavy cotton crew neck T-shirts with screen printed logos on the back), bleached hair, skateboarding shoes (Vans), hoodies before hip-hop, magazines (with in-your-face water photography and cutting-edge graphics) and films - The Endless Summer (1966) whetting appetites for discovery; Big Wednesday (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979) mixing nostalgia with bittersweet political comment; Point Break (1991/ 2015) portraying surfers as ‘outsiders’. Surfing signified both a healthy lifestyle and a rebellious nature. One Malibu local from the 1960s was so light-footed that he was nicknamed ‘Da Cat’ – but you’d better not get on the end of those claws! Mickey Dora possessed an irascible temper and was famous for getting into scrapes.

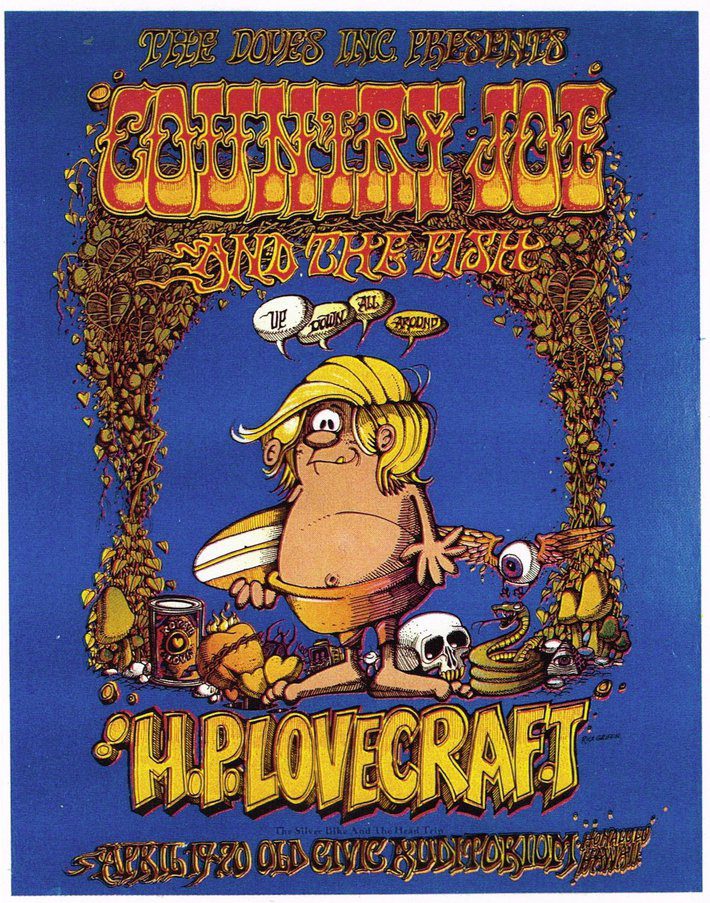

Rick Griffin, the house artist for Surfer magazine, invented the first surfing cartoon hero – Murphy, a goofy kid of the early 1960s who never grew up, then suddenly morphed in the mid ‘60s to create some of the first psychedelic art. An overnight revolution changed the graphic design from jazz-inspired to progressive-rock fantasy. Then the broadcast of surfing cool shifted from California to Australia. As the Vietnam War and the Protest Movement reached a peak, a core of top Australians - led by Nat Young - began using shorter boards, inspired by dolphin-shaped fins and ‘carving’ radical turns. What emerged was an animal arrogance, a slash ’n’ tear approach that had not existed in surfing before. But the aggressive ‘Aussies’ soon cooled out, retired to the country, discovered Byron Bay and the exotic Indonesia experience, showcased in Alby Falzon’s groundbreaking 1971 film, Morning of the Earth. Alby had also started Tracks, a counterculture surf magazine based on the highly successful Rolling Stone. ‘Back to nature’ in turn shaped journalistic style, clothes, music and ‘surfing cool’.

As surfboards got faster and lighter, the seeds of professional and aerial surfing were spawned in the 1970s and ‘80s. And as new surf breaks were developed so beach cultures followed: Biarritz, Byron Bay, Kuta, Rio de Janeiro and Newquay. Surf travel’s notorious independence acted as a model for those who wanted ‘off the beaten track’ experiences, and surfers became pioneers in Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Fiji, Madeira, Morocco, Liberia, the Philippines, the Maldives, Norway and Iceland, while urban surf communities (whose local spot might now be a surf lake) injected exciting new energy into surf culture.

Today a fresh generation of local surfers are re-discovering that various forms of prone waveriding have existed for thousands of years along the coastlines of Africa and around the Pacific and Indian Ocean. In Peru, depictions on pottery of reed fishing canoes being surfed standing up date back to 1,000BC. And in China, poetry describes river-bore riding festivals from one thousand years ago. The image of ‘surfing is cool’ is no longer dominated by the Hawaiian, Californian and Australian narratives, but is now fused with new perspectives from South America, Asia, Africa and Europe. And however ‘surfing cool’ continues to be shaped, the guiding force will be that visceral sensation of riding a wave.